Repricing Sovereignty

Authored by Mark Jeftovic via BombThrower.,com,

Personal Freedom In The Age of Mass Compliance

What follows are a couple of excerpts from the last Bitcoin Capitalist Letter, which was a long-form piece that was a refinement of my overall long term investment thesis. It corrects for my biggest mistake in the previous model: the belief that nation states were in secular decline, and centralized government power was waning.

This may be true for the long haul, but for the next five, ten, twenty years – we’re heading into an era that numerous commentators have been identifying, and I’m looping under umbrella “State Capitalism”.

More specific to our “Great Bifurcation” thesis, what this really means is State Capitalism for the “haves” and mass compliance and (the warmth of?) collectivism for the permanent underclass. UBI is coming out of necessity, and anyone who thinks that isn’t going to be some permutation of social credit (most likely based on personal carbon footprint quotas) is ngmi.

Late Stage Globalism

A paper I came across recently was Nicolas Colin’s Late-Cyle Investment Theory, which came out in June ’25 but Colin was recently a guest on Hidden Forces.

Colin’s paper posits that we are entering the maturity phase of the computer/networking information age.

What got my attention, both from the podcast interview with Demetri Kofinas and then as I read through the paper itself, is how it explains the mechanisms by which late-cycle dynamics force governments toward what we’ve described last edition, a global march toward a kind of “state capitalism” and that “uncomfortable reality I have been grappling with for a few months, that The State and The Economy are in the process of merging”.

We’re seeing a kind of inexorable slide into state-directed capital allocation; it’s taking forms peculiar to its cultural backdrop but it’s happening all over the world.

Russell Napier calls it “National Capitalism”; he also appeared on Hidden Forces a year ago and we covered it in the December ‘24 edition.

WEF luminaries like Marianna Mazzacuto – wholly in favour of the trend – calls it “The Entrepreneurial State”; Tyler Durden over at Zerohedge calls the American expression of it “WHAM” – White House Asset Management.

My favourite version of it is George Gilder’s “Emergency Socialism”, because it captures the exigencies that are making this a priority among governments worldwide.

Colin is somewhat unique in that he argues high public debt isn’t a policy mistake but a structural feature of technological maturity (not sure I agree, tbh).

As he puts it, governments continue borrowing as if the previous growth regime still applies, even as productivity gains plateau and returns diminish.

The numbers are stark:

US public debt at 122% of GDP (255% including private sector)

France at 112% (300% total)

Japan exceeding 260% public (400% total).

Not mentioned in his paper, but I’ll add that Canada’s total government debt (all levels) is 120%, and our private debt on its own is north of 200%.

These levels dwarf anything seen during the 1970s inflation.

The options, as Colin lays them out, are brutally limited, and this shouldn’t come as a surprise to any of us here.

Governments cannot meaningfully raise taxes, any increases can only be performative and symbolic. Those who pay the lion’s share of them have already demonstrated a willingness to relocate if the “tax the rich” slogans translate into excessive action (we’re already seeing anticipatory exoduses from New York City as Mamdami comes in threatening full-on socialism).

Nor can governments cut spending, because various entitlement programs dominate budgets.

Colin thinks that they can’t outgrow the debt because technological maturity means slower productivity growth, which is the core of his thesis.

He may be right, but I don’t think governments believe that – they are looking at AI to ignite a productivity boom that can outpace the debt bubble.

Whether Colin is correct, or governments believe their own mantra about a productivity miracle in the offing, both roads lead to the same place:

There is only one politically viable path, and that is inflation.

“Run it hot”, basically.

But here’s where Colin’s analysis dovetails with our thesis: inflation has consequences.

As prices rise and real rates fall, voluntary demand for government bonds evaporates (this is why we’ve been seeing yields on sovereign debt spiking higher for over a year).

The one common denominator from those we’ve mentioned above (Colin, Napier, Gilder) is that the most likely outcome is financial repression: policies that force domestic savings into public debt through capital controls, regulatory mandates, and banking rules.

This is the merger of the state and capital that I’ve been warning about. It is a type of financial repression, but the quiet bureaucratic kind where your pension fund must hold treasuries, where capital controls prevent you from moving wealth offshore, where the rules of the game are systematically rigged to channel private savings toward public obligations.

Colin frames this as part of a broader institutional fragmentation. Trade wars, he notes (citing David Skilling), are precursors to capital wars.

States that once relied on global capital markets increasingly treat capital as a strategic resource (hence the advent of things like “Strategic Bitcoin Reserves” – my comment, not his).

The open, rules-based order many still assume to be in place is actively unravelling.

Napier talked about all this a year ago and never once uttered the word “Bitcoin”, let alone crypto.

Colin, for his part, sees crypto and stablecoins as part of the emerging new financial system (sound familiar?), and what’s fascinating is how this all maps onto The Stablecoin Standard thesis we’ve been developing.

He sees dollar-backed stablecoins as America’s attempt to extend monetary hegemony into the digital age, essentially creating a new channel for petrodollar-style recycling where foreign demand for USDT and USDC indirectly finances US government debt.

No surprise here, but it contains an inherent tension: stablecoins work precisely because they route around traditional banking, yet that same feature makes them harder to control when geopolitical pressures mount.

The implication for us is clear and it emerges in a kind of “Barbell trade” portfolio that both recognizes the reality of State Capitalism while also hedging for it via the simultaneous emergence of a parallel system (more on this below).

The big wake-up call for me, is that The State Is “The House”. I’ve spent most of my adult life thinking that it was on its last legs, that at some point a Geopolitical Minsky Moment would demolish the entire scaffolding, and then sound money and free markets would assert themselves.

I was wrong. I’ve now realized that.

The general public will never not believe in the legitimacy of “The State” (even though they may dispute who currently occupies the machinery). It’s baked in since childhood – and it won’t matter that their leaders debase the currency, leach away their wealth, send their children to die in turf wars or even load their neighbours into boxcars. The masses will always believe that The House is legitimate, inevitable and necessary.

With all that said, I still do think that there will be a geopolitical Minsky moment, a kind of global, macro “force majeure” that resets the table, simply because the fiat currency system is well past its “use by” date – but make no mistake, the only thing that happens to The House in the aftermath is that some other faction takes over the lease. And the masses will then dutifully follow the new boss.

The only antidote to this is on the individual level. Independent thinking and independent wealth. That’s it.

If you have a compassionate streak and you want to help the masses or uplift the poor, you have one way to do it: give them the means, motive and opportunities to lift themselves at an individual level – education, mentorship, motivation, angel investing, scholarships, introductions.

One may ask what the exact change in thesis is; if we’re still long Bitcoin, we’re still invested in what we think is the emerging new financial system, we’re still long picks and shovels.

Before we get to it, we have to put a couple more pieces on the table.

The picture we see emerging is this:

Increasing numbers of plebs are “checking out” of the system, trying to degen their way to wealth, and not even bothering to vote for a system that has essentially abandoned them (referring to our write up on The Prison of Financial Mediocrity in the full edition)

AI is killing not only jobs, but entire career paths. UBI is moving past being part of the conversation – I expect 2026 to be a pivotal year in turning it into reality in multiple jurisdictions.

Whoever still believes there’s a functioning system in place, does so for the simple reason that they are banking on it to save their asses: hence the growing populist surge on both sides of the political spectrum – but “democratic socialism” and collectivism seem to hold characteristically peculiar attraction for vast swaths of the public.

The final piece in all this is the unrelenting crack-up of the global financial system itself and the geopolitical scaffolding that, until recently, seemed immutable.

I reiterate my old prediction that Donald Trump will be the penultimate president of the United States as they are understood today. Whoever comes after will be the last. And then the US will morph into something else, similar to the breakdown of the USSR in the early 90s.

The same is happening in Canada – where there are now three separatist movements: Quebec, Alberta and now Saskatchewan.

The Eurozone will likely crack up under its own internal tensions and secessionist movements are poised to gain momentum the world over.

How do we reconcile that with an era of Big Government and State Capitalism?

There will simply be more states: a multi-polar world, and different jurisdictions will govern with varying levels of heavy-handedness and interventionism.

Singapore, for example, is for all intents and purposes an authoritarian enclave – under the singular rule of the People’s Action Party since independence, and everybody who lives there seems fine with that. The trains run on time, there are very low levels of corruption and street crime is practically unheard of.

They’ll cane you for chewing gum in the subway (harsh? Try riding the TTC in Toronto without getting stabbed by a mental patient), and they’ll execute you for serious crimes, but there are no “immigration discounts” on sentencing (in November, two men were hanged for trafficking heroin, one a Singaporean, the other, Malaysian).

Singapore is no libertarian paradise, but there is also pretty well zero possibility that any purple-haired Trantifa berserkers are going to shoot up your kid’s school, or that some liberal arts soy-boy in a keffiyeh will smash your face in with a brick on New Year’s Eve.

So there’s that.

Parag Khanna, in his elite-class best-seller “Technocracy In America: Rise of the Info State”, said the governance model of the future should be some manner of Swiss-Singapore hybrid. I remember being both bemused and mortified when I first read that (it came out in 2016) …in the intervening years, I find myself thinking we may do OK with a touch of both:

“What model should post-authoritarian or newly democratic societies pursue: Swiss-style organic economic diversification or Singapore-style managed innovation?

The answer is both. Having lived for stretches in both these small countries, I’ve come to see that despite their enormous differences, what matters most is that Switzerland and Singapore are both verifiably democratic and rigorously technocratic at the same time.”

Khanna cites Harvard’s Michael Porter and Richard Rosecrance, who forecasted an emergence of a “market state” era.

Also,

“business strategist Keniche Ohmae, in his book The Next Global Stage (2005), argued that urban agglomerations of city-states resembling the medieval Hanseatic League would become the world’s power centers.”

When you take a step back, it’s not that different from the mosaic of competitive (not combative) sovereignties posited back in The Sovereign Individual (or, Snow Crash).

It just turns out that Khanna arrived as a similar conclusion from a different angle. If I’m honest, my initial reaction to it probably owed much to Khanna’s involvement with the WEF.

As a recent guest on the Canadian Bitcoiners Podcast once quipped, almost off-handedly, “the wealthy never suffer in any society”.

In places like Singapore – and the innumerable micro-sovereignties that will spring up over the coming years – there will be due process and basic rights (Singapore has a constitutional guarantee on free speech, with a lot of escape hatches for the government in cases of public order, hate, etc. – the same thing is happening here in Canada, and around the world).

But realistically, it will probably take deep pockets to be able to exercise those rights. In Canada we have an expression to describe what happens to property owners who use deadly force against violent home invaders, “The process is the punishment”.

It means if your door gets kicked in by some low-IQ imports who are already out on bail for doing this previously, and you blow their heads off with a legally owned shotgun, you will be charged and forced to stand trial. After a few years, and several hundred thousand dollars in legal fees, you’ll likely prevail in court. If you don’t have the resources to fight that battle, you’ll take a plea deal and spend some time behind bars with exactly the same types of people you just defended yourself against.

Remember our maxim: “In the future, it’ll be a lot more expensive to be free”.

Meanwhile, the bottom tiers of the wealth pyramid across most jurisdictions (the permanent underclass) are going to embrace collectivism, populism and wind up with varying degrees of authoritarianism.

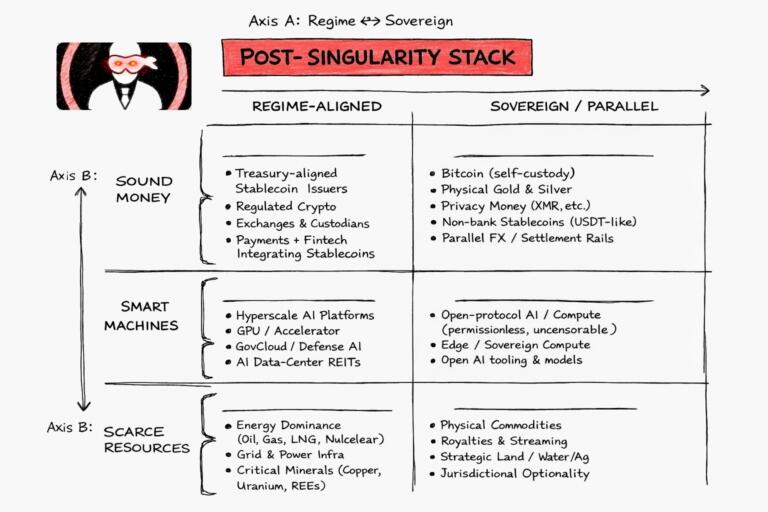

The Post-Singularity Stack and the SoS Portfolio

This is the tightest wrapper I could come up with for everything I’ve been trying to set out in this issue.

Due credit goes to Addison Wiggin, from the Grey Swan Fraternity, who recently put out a piece entitled “Repricing Legitimacy”. It touches on many of the same themes we’re monitoring here: the widespread disaffection of the younger generations, and the loss of faith in legacy institutions – albeit, as we’ve noted above, somewhat ironically juxtaposed with a renewed enthusiasm for Big Government and even collectivism.

“Our job isn’t to pick a slogan or a side. It’s to recognize where legitimacy is being rebuilt, where it’s being faked, and where it’s quietly draining away.

Revolutions without plans tend to end in terror and sorrow. Systems without trust eventually seize up.

Cycles don’t care what we believe. They respond to balance. And balance, right now, is being renegotiated almost everywhere at once.“

Drawing on source material mentioned earlier, plus a few others:

Viktor Shvets’ “Twilight Before The Storm”

Jeffrey Towson’s “What Would Ben Graham Do Now?”

Daniel Bell’s “The China Model”

The common theme seems to be that they are books which filled me with revulsion and dread the first time I read them.

Shvets’ thesis is point blank: the old neoliberal capitalist consensus has collapsed and no new model has yet emerged, but all indications are that it’ll include some kind of socialism (my extension on this is that we’re headed for a two-tier system of techno-socialism for the masses, and state capitalism for the asset holders).

If you hear Shvets on any interviews, he usually blames the markets for breaking down – saying, in effect, that “the market model has been discredited”. I would beg to differ, saying that the market functioning has been completely coopted by government interventionism and fiat debasement, but at the end of the day it doesn’t matter. The dysfunction is real.

He makes frequent references to something called the “Fujiwara Effect”, a meteorological term for when multiple hurricanes converge into a single, humongous, cataclysmic storm. The analogy here is the compounding of multiple negative cycles: financial, with the debt bubble; technological, with the existential disruptions coming from AI – and he also puts “climate change” in there, which I actually view as the one thing we don’t have to worry about, at least not now.

It’s still a fitting term for what we’re headed into: some kind of transition that won’t be incremental, but “rupture”-like.

Towson, whose book is over a decade old, reframed value investing as not only a game of mental chess with “Mr. Market”, but as one where “Mr. Government” had entered the chat. Investors and entrepreneurs would henceforth have to take the ever-increasing regulatory and ideological biases of The State into account when making their allocation decisions.

Daniel Bell himself defended criticisms that he was extolling a China-style command economy, which he maintains he was not, but that the point of his book was that nobody can dispute China’s results in operating that way. It works. Or at least it did (they too, have an enormous, untenable debt bubble, just like everybody else).

If there is a common aspect to these models it’s that policy starts to crowd out price discovery.

We’ve been dancing around this realization for a long time; this is what I’ve been intuiting every time I said that shorting anything was a fool’s errand because markets are now structurally hardwired to go up – more so than at any other time in history.

That’s fiat debasement at work, and it puts the entire universe of assets on an escalator, and from there it’s a matter of picking what will outperform the rate of decay in our denominators.

Tyler Durden’s phrase “White House Asset Management” (WHAM) is telling us that intrinsic value is now a political function, at least partially so. Imagine being short MSTR only to wake up some morning and find out that Trump put out a tweet during his morning dump announcing that the US government just took a 10% stake in MSTR, MARA and HUT/ABTC.

Nobody should be surprised if that happens. Not anymore

For many years I’ve taken pains to chart a largely libertarian, if not anarcho-capitalist path, the crux of which was trying to conduct myself with no regard to who was in power or which party formed the government.

I basically tried to tune out The State. I’ve conceded that it’s become much harder to do that since COVID, but I was still making my investment and capital allocation decisions from a market forces perspective.

And that is what is changing now. Our overall thesis may be unperturbed: The Great Bifurcation, Monetary Regime Change, etc. – but I am now grudgingly acknowledging that The State is going to impact our economic calculus more than I’d care to admit.

Those above-mentioned books which filled me denial and dread when I first read them, I’m now re-reading to adjust my investment theses around them.

I’m not exactly happy about it, but here we are…

Let’s talk SOS (Sovereign vs Serfdom):

If we’re going to stipulate that The State, “Mr. Government” (or “Mr. Regime” as I began to frame it mentally) is now part of the calculus, one of the places to start is to look at the largest economy in the world – The United States – and look at what its stated, national strategic objectives are.

The “economic security” objectives include: critical supply chains (logistics) and materials, energy dominance, reviving the defence industry, and growing financial sector dominance.

We know that energy dominance doesn’t mean windmills and solar, it means nuclear, oil, and natgas.

We also know that financial sector dominance will have Bitcoin, blockchain, crypto and stablecoins baked in.

And, big surprise, more military spending.

When I looked at all this and realized that all major powers are jockeying around these same themes, what came to mind for me was a kind of barbell positioning between “Mr. Regime” and a Parallel System (including “freedom tech”) across two axes:

Axis A: Serfdom vs Sovereign

Regime-aligned: are companies and assets that directly benefit from various national security strategy priorities (energy dominance, reindustrialization, defense industrial base, financial/AI leadership).

Sovereign / Parallel: Bitcoin, gold, privacy, decentralized rails and jurisdictions that hedge State Capitalism and what I sometimes call the “monetizing serfdom” trade.

These are positions that get us through whatever this is happening right now and over the next five to ten years.

Axis B: The “Post-Singularity” stack

Sound Money: Bitcoin, precious metals, future fintech

Smart Machines: AI / HPC / Big Data

Scarce Resources: energy, metals, base commodities

These are the companies and resources ushering in or underpinning “what comes next”.

Putting it all together

I touted this edition as a “major revision to the thesis”, however as I worked my way through it, what became apparent to me was that not a lot had changed within the thesis itself, except perhaps in timing:

- The Great Bifurcation was coming => TGB is here

- Governments and institutions are out of their depth

- Bitcoin will make a place in the next financial system => Bitcoin has taken its place within the emerging financial system

If the overall components and mechanics of the thesis haven’t changed – then what exactly did? Because something sure feels different to me.

I guess the big shift is from an overall optimism that humanity was going to level up en masse through the separation of the State and money (“fix the money, fix the world”), and admitting that was extremely naive.

It comes down to two things:

#1) Big Government is waxing, not waning:

Despite our governments and institutions being legacies of the industrial age, trying to linearly extrapolate their approaches into a non-linear world, their influence is not waning – as I have been positing since the aftermath of the pandemic.

The State is asserting itself ever more into the private sphere, everywhere.

I’ve made passing references to “a last gasp of Big Government” and the Nanny State in the past, but I think I under-emphasized it. This so-called “last gasp” will persist for a long time in the context of our lives. It could be a couple of decades, or more, before this plays itself out.

#2) I’ve completely misread the public mind

Again, thinking the demise of institutional credibility and loss of faith in an unaccountable and insular ruling class coming to a head during COVID was a secular wave.

That also appears to be wrong. It was an aberration and the general public has settled back into lethargy and compliance.

The combination of these realities pushes us toward the “Mr. Regime” side of the investment thesis, which is basically monetizing servitude, and on a certain level, that just feels wrong.

Aren’t we supposed to try to educate the masses? Make them understand how screwed they are if they don’t take massive action right away?

Our better nature may say so, but let me tell you a story about that impulse… (a true one):

In 1984, an unknown social psychology professor put out a book that was intended to be a consumer awareness tool designed to “pull back the curtain” on how people are manipulated.

The author described himself as a lifelong “patsy” and “easy mark” who wanted to educate the general public on the tactics of “compliance professionals” (like salespeople, marketers, nudge units and propagandists) so that they could defend themselves.

The book flopped, his publisher going so far as to withdraw promotion and publicity funds, citing that it would be like “throwing money down a pit”.

Nobody cared.

That book was eventually discovered by the very people who it was intended to expose: the marketing industry.

Robert Cialdini’s “Influence” is now an evergreen staple of the business world, having been re-released in an expanded edition, and has sold over 7 million copies worldwide.

This anecdote is both depressing and indicative of the world we live in – a microcosm for everything.

You thought Bitcoin was going to emancipate the masses from the tyranny of central banking?

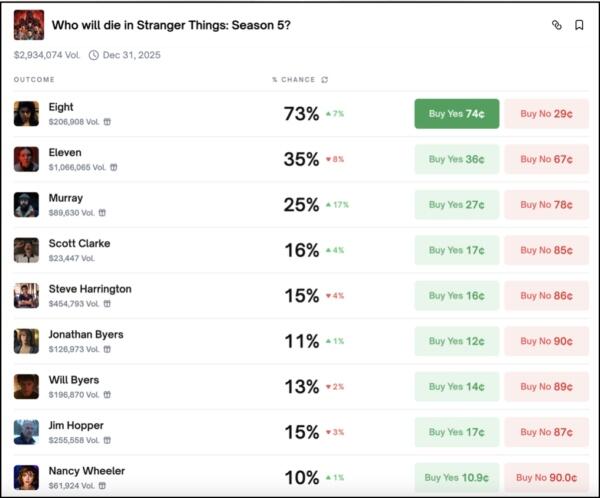

The masses don’t care. They’re busy piling onto Polymarket and betting on which Stranger Things character is going to die in the finale:

You know who does care about Bitcoin, now? JP Morgan. Wells Fargo. Citigroup.

As TFTC notes, “14 of the top 25 US banks are now building Bitcoin products”:

Note also how a couple are building their Bitcoin products for “HNW Clients Only.

And that’s why if we want to stay on the right side of The Great Bifurcation and have the means to chart our own paths through this period of State Capitalism, we’re going to have to do it individually – and recognize that in the future, it’ll be a lot more expensive to be free.

That’s why the revised thesis carries a cynicism that’s uncomfortable. Any remaining altruism I felt toward a public that would rather ignore, or even punish the messenger than act on the message has to be quelled, and any civic-mindedness I had left has to be channeled accordingly (mentorship, curation, lead by example, etc).

What bothers me the most about this, was that in the past there was no existential impetus to break oneself out from the crowd. Everybody had the perfectly reasonable option of simply fitting in: you could get an education or a trade, work for a living, buy a house, raise a family, put your kids through college and just live a quiet, middle class life.

My dad worked on the shop floor in a General Electric plant for over thirty years, after which they gave him a pen for his retirement and a pension that my mom collected for another 17 years after he died. My parents were probably among the last generation of truly working/middle class people to live, work, save and retire.

All that is over. A bygone era.

Serfdom or Sovereignty (“SoS”) – that’s the choice now and most people aren’t even aware of it, and when they see somebody choosing sovereignty it looks downright heretical to them.

We can’t help these people, and that makes me sad, even if the majority of them would gleefully stone me to death in the street if the TV set ever tells them that the reason their livelihood is gone and their savings have been vaporized was because of “Bitcoin speculators” and goldbugs.

Most people are stupid. Especially when they act in numbers. If you’re reading this letter, you aren’t one of them.

The next edition of The Bitcoin Capitalist Letter, with more on the Post-Singularity Stack, should be out next weekend. Bombthrower readers can get a special trial offer here

Sign up for the Bombthrower Mailing List here and get a free copy of The Crypto Capitalist Manifesto.